History

CONNEMARA RAILWAY

“Closed to steam in 1935…opened to discerning guests in 1998!”

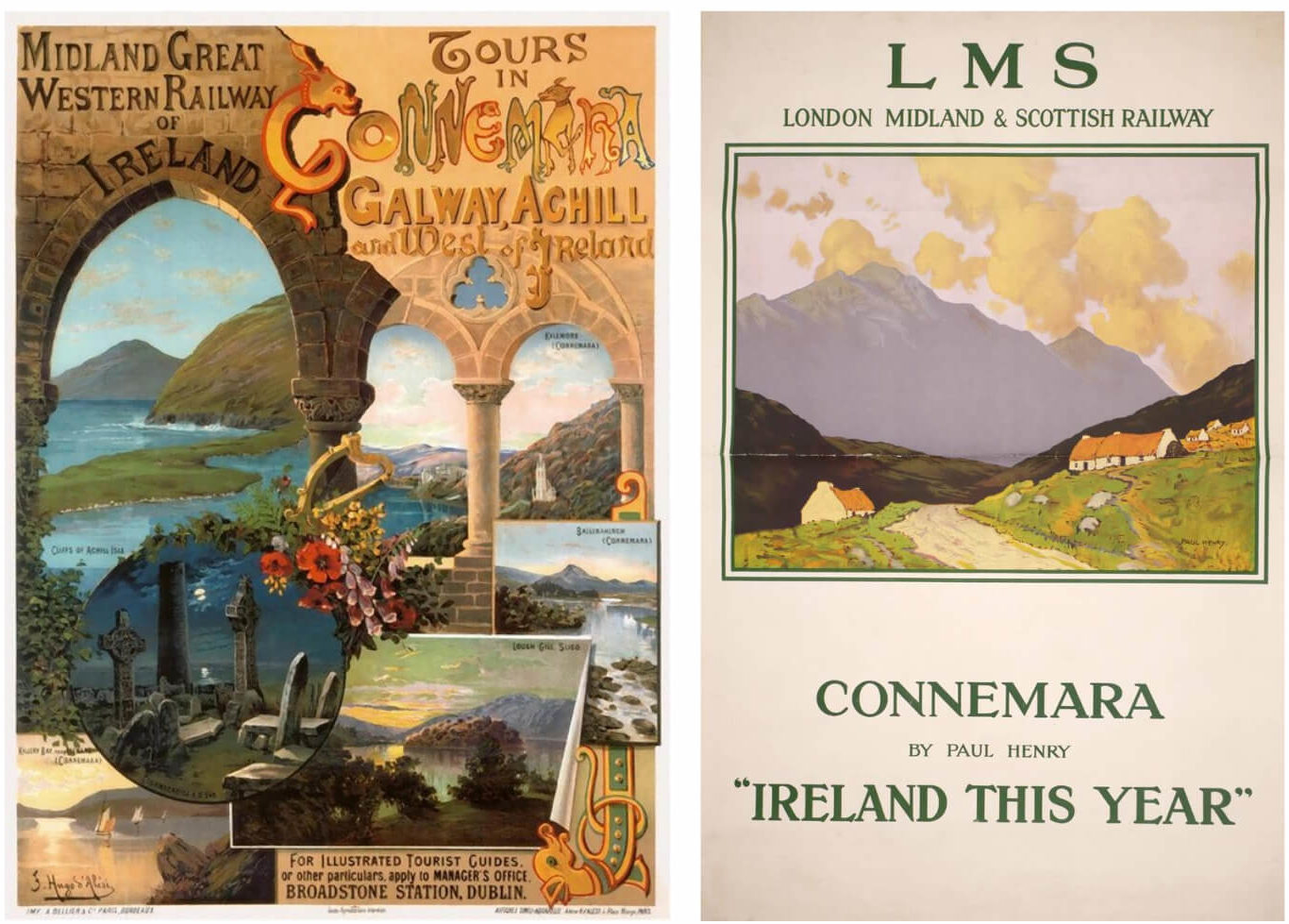

The Galway Clifden railway was opened officially on the 1st of January 1895 and ran through villages including Moycullen, Ross, Oughterard, Maam Cross, Recess, and Ballynahinch, ending in Clifden. The steam train ran at a financial loss for 40 years carrying freight and passengers through Connemara. It was operated by the Midland Great Western Railway Co. but a change in governing policy in 1935 resulted in the closure of the railway line, much to the detriment of the social and economic future of Connemara. Immediately after the closure the steel tracks were lifted and sold on as scrap metal; rumour has it that the steel was used in the making of munitions used in WWII.

The railway buildings and site later became home to Millars Connemara tweed mills. Millars tweed were the largest employers in the area and produced their world-famous tweed from here until the mid-90’s when the mill then ceased manufacturing. The site and surrounding listed buildings lay in disuse until 1998 when a huge development and restoration project was completed by local businessman John Sweeney, which eventually became the Clifden Station House Complex you see today. The old Stationmasters house is now the Signal Bar & Restaurant, incorporating many of the original features including the old railway platform and railway memorabilia. The old engine house is now a museum with a particular emphasis on the local historical connections with Marconi, pioneering pilots Alcock & Brown, John D’Arcy the founder of Clifden, and the Connemara Pony.

MARCONI WIRELESS STATION

Guglielmo Marconi caused a communications sensation when he transmitted wireless messages from his station at Poldhu in Cornwall to Newfoundland on 12th December 1901. Having received a grant of $80,000 from the Canadian Government to build a station at Glace Bay in Nova Scotia, he commenced the task of perfecting wireless communication with Poldhu from late 1902. He experienced extreme difficulty in providing commercially viable communications and decided to move his easterly station as far west as possible and decided on Clifden (Derrigimlagh) after making tests at a number of sites.

The station was not officially opened until 17th October 1907, when commercial signalling commenced between Clifden and Glace Bay. It was a sight to behold, with the huge condenser house building, the power house with its 6 boilers, and the massive aerial system consisting of 8 wooden masts, each 210 feet high extending eastwards over the hill for a distance of 0.5 kilometres. The aerials gave off sparks which could be heard in the distance, indicative of the huge power and voltages involved (150KW at 15,000 volts).

As time moved on, advances were made in the technology and a more powerful station was built at Caernarfon in North Wales. The Clifden station was attacked by republican forces in July 1922 and some buildings were damaged. The Marconi Company sought compensation from the new Free State government, but this did not materialise. The station was closed shortly after. The area has now been transformed into a 5 kilometre looped walk through the bog which is home to a memorial cairn dedicated to the pair. Hire a bike, navigate around tiny lakes and peat bogs, and discover this unique and beautiful area. The walk is augmented by a number of attractive features which are designed to engage visitors and encourage them to interact with the history of the location.

ALCOCK & BROWN

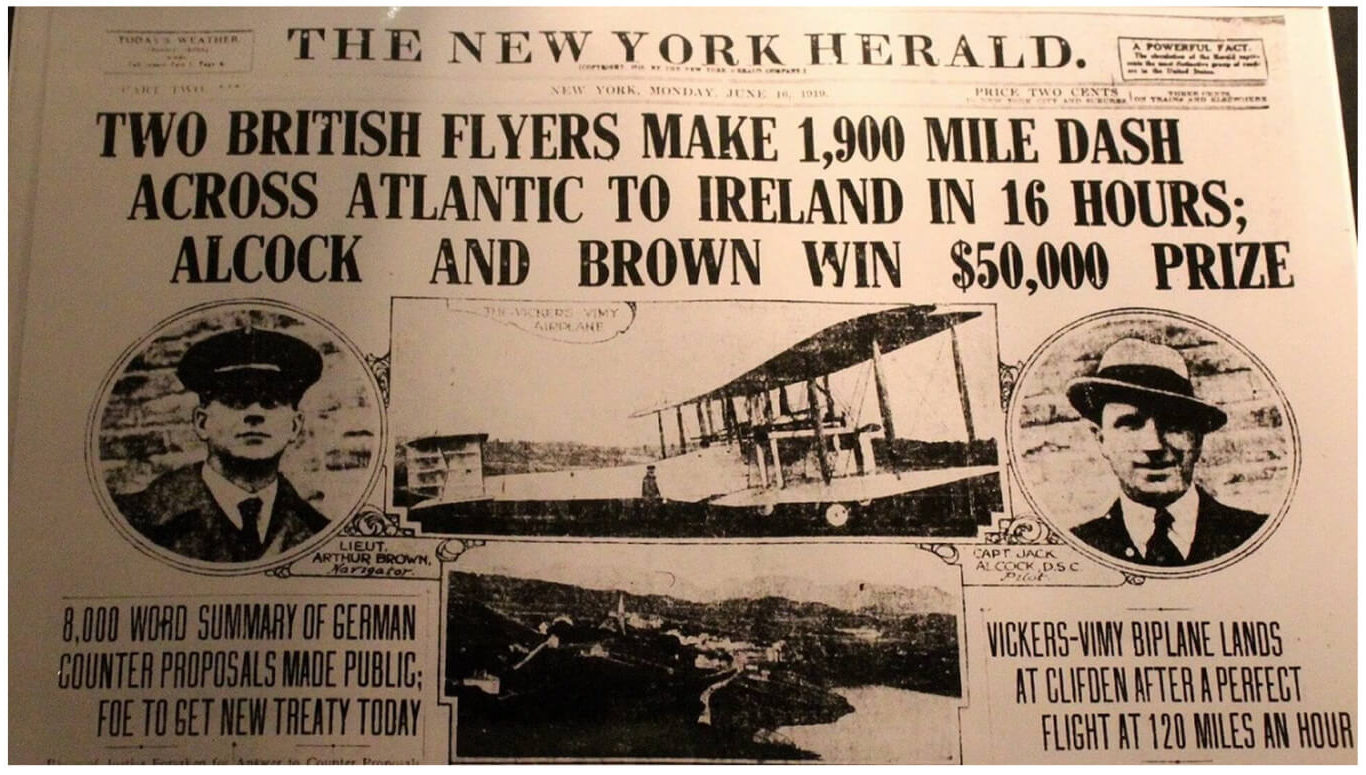

The first transatlantic flight was achieved in 1919 with the arrival of a Vickers-Vimy biplane behind the Marconi wireless station at Derrigimlagh, 4 kilometres south of Clifden. On-board were two British airmen, Captain John Alcock (pilot), and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown (navigator). The aeroplane had taken off from Lester’s Field in St John’s, Newfoundland at 4:12 p.m. GMT the previous day and arrived at Derrigimlagh, Clifden, County Galway at 8:40 a.m. GMT on Sunday 15th June. The distance covered was a little less than 1,900 miles. The flight time was 16 hours 28 minutes.

The successful flight had won the two fliers a £10,000 prize and a place in aviation history. Competition for the prize was intense and several aircrafts had gathered at St John’s in preparation for the challenge; one attempt had already failed. The average speed during the Atlantic crossing was 120 miles per hour. On takeoff, the Vickers-Vimy carried 865 gallons of petrol and 40 gallons of oil. On arrival at Derrigimlagh, she still carried sufficient fuel for a further ten hours flight. The flyers wore electrically heated clothing, Burberry overalls, fur gloves and fur-lined helmets. The battery for heating their clothing sat between them in the cockpit. They carried with them 300 private letters, the first transatlantic airmail in history.

Crossing the Irish coast, Alcock and Brown spotted the tall masts of the Marconi wireless station at Derrigimlagh. Recognizing their location, Alcock decided not to go any further. Switching off his engines, he glided towards what he thought to be a level stretch of ground behind the station. The wheels touched down and ran on a short distance, before coming to a stop as they sank into the bog. The nose dipped and the tail lifted, and fuel began leaking into the cockpit. The airmen scrambled to safety, stepping onto Irish soil.

Clifden Station House is an ideal centre for exploring Connemara and all its famed attractions. It’s a fantastic example of old world Ireland being thoughtfully restored.